Northern shifts in the migration of Japanese glass eels to subarctic Hokkaido Island over the past three decades

Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute,

The University of Tokyo

Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Science,

The University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo Ⅲ/GSⅡ

HOKKAIDO UNIVERSITY

1. Key Points

Field observations conducted from April to July 2021 in a river in southern Hokkaido reported in this study, identified for the first time, the potential recruitment period of juvenile glass eels in Hokkaido may have commenced in May and concluded in July.

The long-term trend of Japanese eel※1 recruitment to Hokkaido was examined using a three-dimensional particle-tracking model based on ocean reanalysis JCOPE2M※2, which showed increased recruitment in northern Japan and decreased recruitment in southern Japan during 2014–2023 compared to 1994–2003, that was attributed to the shift in the Kuroshio.

Simulated recruitment in northeastern Japan indicated an increase in southeastern Hokkaido and a decrease in the Tsugaru Strait, which was linked to the northward shifts of the Kuroshio/Kuroshio Extension and Oyashio, and strengthening of the Tsugaru Current.

Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica)

One of the most important eel species in the western Pacific and is classified as endangered in IUCN red list.

JCOPE2M

The data assimilated ocean reanalysis product provided by Application Lab of JAMSTEC, and is available from 1993 to present.

(https://www.jamstec.go.jp/jcope/htdocs/e/distribution/index.html)

2. Overview

Observations of Japanese eel Anguilla japonica recruitment on Hokkaido’s coast in 2020 revealed a poleward shift of the species’ northern limit by several hundred kilometers. Field observations conducted from April to July 2021 in a river in southern Hokkaido, identified for the first time the potential recruitment period of juvenile glass eels in Hokkaido, suggesting that the recruitment season may have commenced in May and concluded in July. The long-term trend of Japanese eel recruitment to Hokkaido was examined using a three-dimensional particle-tracking model based on JCOPE2M ocean reanalysis. The simulation covered Taiwan and Japan showed increased recruitment in northern Japan and decreased recruitment in southern Japan during 2014–2023 compared to 1994–2003, which was attributed to the shift in the Kuroshio. The simulation in northeastern Japan exhibited patterns consistent with the natural variation in eel abundance observed across 95 rivers in southern Hokkaido in 2022, with higher recruitment in southeastern Hokkaido and lower recruitment in the Tsugaru Strait. Simulated recruitment trends from 1994 to 2023 indicated an increase in southeastern Hokkaido and a decrease in the Tsugaru Strait, which was linked to the northward shifts of the Kuroshio/Kuroshio Extension and Oyashio and the strengthening of the Tsugaru Current. These findings suggest that long-term fluctuations in ocean currents significantly influence the northern limit of anguillid eel habitats, highlighting the impact of changing oceanic conditions on their natural distribution.

This research was published in Ocean Dynamics on January 7th (JST). This study is supported by JSPS KAKENHI (23K03503 and 23K05351).

Yu-Lin K. Chang1,*, Kentaro Morita2, Kanta Muramatsu3, samu Kishida4, Mari Kuroki5,6

2. Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo

3. Graduate School of Environmental Sciences, Hokkaido University

4. Wakayama Experimental Forest, Field Science Center for Northern Biosphere, Hokkaido University

5. Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies, The University of Tokyo

6. Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo

3. Background

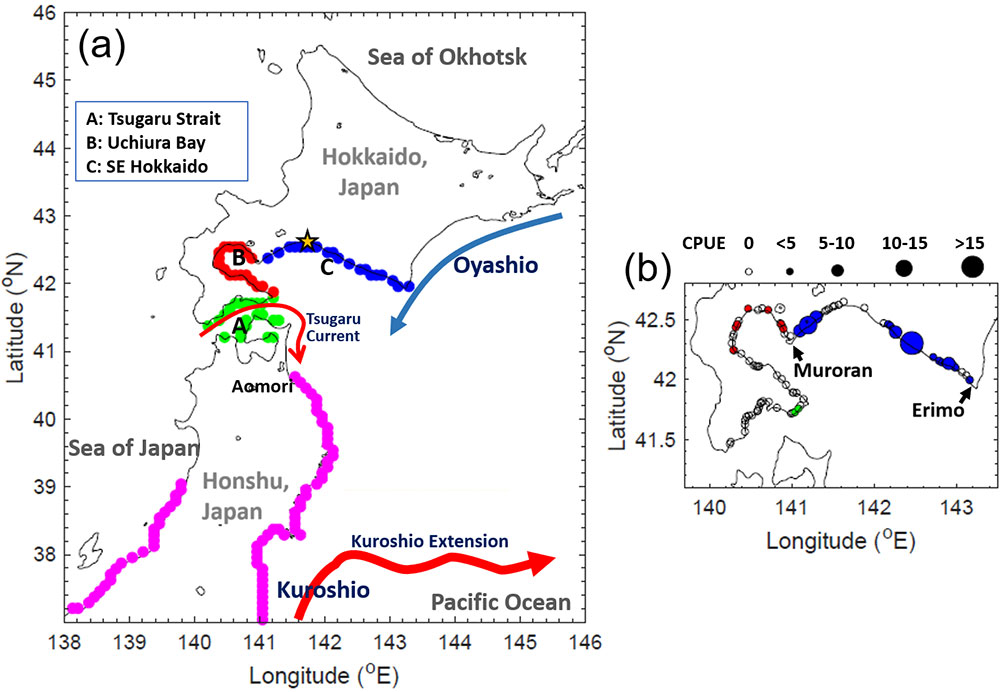

The life cycle of catadromous anguillid eels is complex. The Japanese eels are born in the ocean along the West Mariana Ridge, and the newly hatched leptocephali are transported by the North Equatorial Current and the Kuroshio to their growth habitats in East Asia, including Taiwan, China, Korea, and Japan. Historically, the northernmost recorded region of glass eel recruitment was Aomori Prefecture (~41° N, Fig. 1a). In 2020, glass eels were collected on Hokkaido Island in late May (Morita and Kuroki 2021), marking the first documented recruitment in this region and extending the known northern limit of Japanese eel distribution. Due to the lack of early glass eel sampling in Hokkaido, it remains unclear whether glass eel recruitment to the region has occurred for years or has only recently begun. This study combined the on-site surveys with a numerical approach, offers a valuable opportunity to clarify the recruitment dynamics of glass eels in Hokkaido. Based on the observational results, the study simulated the long-term dispersal of virtual larvae to Hokkaido over three decades (1994–2023) using a three-dimensional particle-tracking method. The simulation revealed year-to-year variations and a long-term trend of increasing v-larvae dispersal toward Hokkaido. Moreover, the study tentatively explored the possible causes of the increasing and decreasing recruitment trends in various parts of Hokkaido, which may be linked to changes in ocean climate.

4. Outcome

Field observations conducted from April to July 2021 in a river in southern Hokkaido (Fig. 1a), as reported in this study, identified for the first time the potential recruitment period of juvenile glass eels in Hokkaido may have commenced in May and concluded in July.

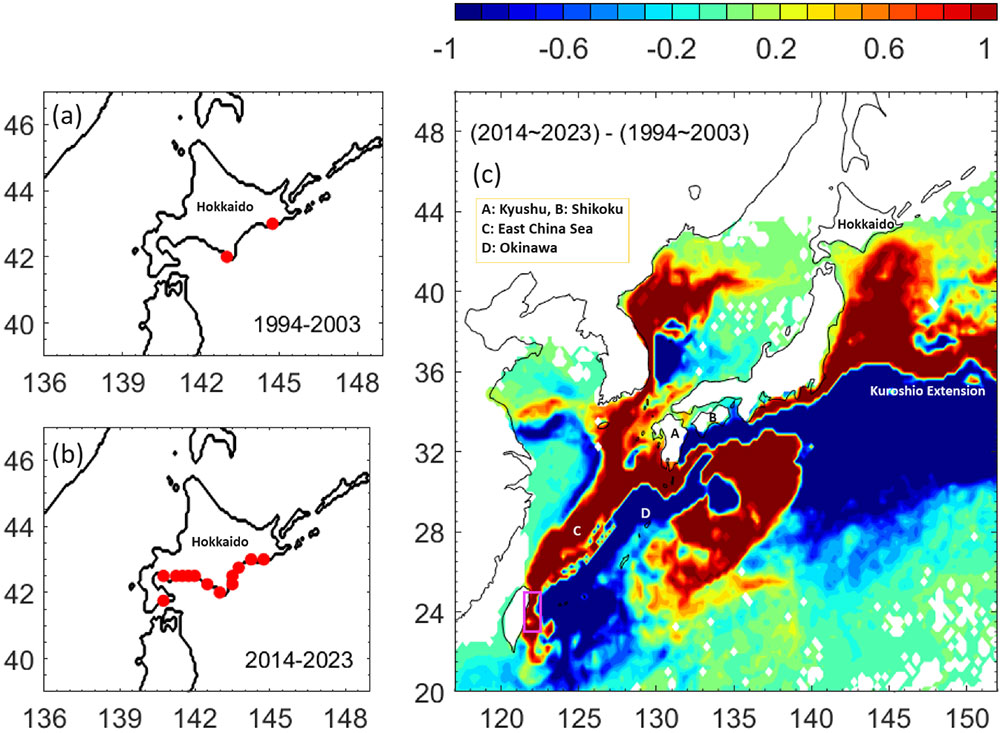

The long-term trend of Japanese eel recruitment to Hokkaido was examined using a three-dimensional particle-tracking model. Virtual larvae were programmed to swim both horizontally and vertically, in addition to being transported by ocean currents, after their release near eastern Taiwan (Scenario 1) and northeastern Japan (Scenario 2).

Scenario 1 showed increased recruitment in northern Japan and decreased recruitment in southern Japan during 2014–2023 compared to 1994–2003, which was attributed to the shift in the Kuroshio (Fig. 2). In Scenario 2, focusing on local processes near Hokkaido, the spatial variation in estimated glass eel recruitment exhibited patterns consistent with the natural variation in eel abundance observed across 95 rivers in southern Hokkaido in 2022, with higher recruitment in southeastern Hokkaido and lower recruitment in the Tsugaru Strait (Fig. 1b). Simulated recruitment trends from 1994 to 2023 indicated an increase in southeastern Hokkaido and a decrease in the Tsugaru Strait. The increased recruitment to southeastern Hokkaido was linked to the northward shifts of the Kuroshio/Kuroshio Extension and Oyashio, which weakened the southward currents in the confluence zone of the Kuroshio/Kuroshio Extension and Oyashio. In contrast, reduced recruitment in the Tsugaru Strait was associated with the strengthening of the east-flowing Tsugaru Current.

Fig. 1 (a) Map of northern Japan and schematic plot of major ocean currents and the defined regions (A: Tsugaru Strait, B: Uchiura Bay, and C: southeastern Hokkaido) for the analysis. Magenta dots indicate historical recruitment locations of Japanese eel larvae. The yellow star marks the site of glass eel surveys conducted in 2021. (b) Survey locations and catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) of yellow eels in southern Hokkaido during 2022. The blank dots denote zero CPUE, while colored solid dots indicate nonzero CPUE, categorized by the regions defined in (a)

Fig 2 virtual larvae recruitment to Hokkaido during (a) 1994–2003, (b) 2014–2023, and (c) the normalized v-larvae visitation frequency differences between 2014–2023 and 1994–2003, with v-larvae released east of Taiwan (magenta box).

4. Outcome

The two years of glass eel surveys do not imply that the absence of records before 2020 was due to nonexistent recruitment. Instead of focusing on exact simulated recruitment rates, this study emphasizes the variations in the potential effects of ocean currents. Consequently, while this study does not conclude that Japanese eel recruitment to Hokkaido was absent in earlier years, it suggests that the likelihood of natural recruitment to Hokkaido has increased in the recent 20-30 years. To ensure effective conservation and management of Japanese eels, future research should comprehensively examine trends in the species’ natural distribution, account for long-term changes in ocean currents, and predict shifts in their distribution.

For this study

Researcher Yu-Lin Chang, Research Institute for Value-Added-Information Generation (VAiG), Application Laboratory (APL), Environmental Variability Prediction and Application Research Group, JAMSTEC

Associate Professor Mari KUROKI

Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies and Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies, The University of Tokyo

Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences and Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Tokyo

Professor Kentaro MORITA

Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo

Professor Osamu Kishida

Field Science Center for Northern Biosphere

Hokkaido University

For press release