A Glimpse of What's Below: Logging While Drilling2012年04月30日

このレポートは、Scientific American誌ブログに掲載されています。

Greetings from Drilling Vessel Chikyu! We are floating precisely at N37’ 57” E143’54”. I know we are precisely there because this unusual ship with its five working thrusters can maintain position to within meters. The sixth thruster was damaged on March 11, 2011 when D/V Chikyu, with full crew and elementary students aboard, when the tsunami caused by the Tohoku earthquake arrived at the port of Hachinohe. Thanks to quick thinking by the captain and crew, no one onboard was injured and the children were returned safely to land.

This memory is fresh in the minds of the crew and science party aboard this ship, many of whom experienced the events of March 11. The earthquake was larger than expected for this part of the coast, and the seismological community has been very active in the past 13 months revisiting everything we used to know about earthquake hazard. What’s more, the tsunami generated by this earthquake was bigger than expected ? as you have seen in the photos and videos of waves topping the seawalls in towns along the Tohoku coast. For its size, this earthquake was alarmingly effective at creating a tsunami wave.

Why? What was so special about this earthquake? Clues started emerging in the days and weeks after March 11. Japan has the most detailed network of seismometers and GPS stations, all collecting data in real time, of any country in the world. The seismometers recorded the seismic waves generated by the earthquake, and the GPS stations tracked the motion of the Japanese islands toward the deep ocean trench. Data were collected from sensors on the ocean bottom that recorded the changes in water depth related to ground deformation, ships studied the bathymetry, which showed the horizontal displacement of the edge of the North American plate toward the west.

LWD paradise!2012年04月28日

Data from the record-breaking JFAST hole turned from a trickle into an avalanche last night. The logging while drilling (LWD) tool measures a variety of physical properties of the rock penetrated by the drill bit. During the drilling operation, measurements are sent back up the drill string to the ship via a pressure-pulse in the drilling mud. We were receiving these measurements throughout the drilling, watching the monitor for a new point every 2 minutes. The communication system transfers data at a much slower rate than data are collected, so the majority of the measurements is stored locally on memory inside the tool itself. After the decision was taken to stop penetrating further into the subsurface, the tool was withdrawn and arrived on deck yesterday.

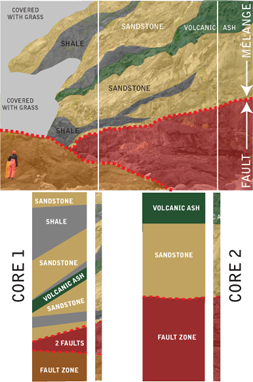

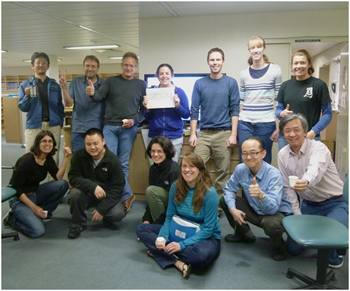

The new data were immediately downloaded from the memory inside the tool and the logging staff scientists and contractors got to work processing to make them available to the science team. We now have huge print outs of the entire section penetrated by the LWD hole, as well as the digital versions of the data. It’s like a treasure trove of information suddenly arrived on deck! Everyone in the science team is fascinated to see what the results show: the resistivity measurements and images and the gamma ray measurements give information on the different rock types, various deformation features, and the stability of the hole itself. But the big question on everyone’s mind is ‘where is the earthquake fault?’ The logging while drilling scientists are in overdrive getting the data processed, and interpretations developed. Several scenarios are possible based on the LWD data so we might need the long-term observatory data and the core observations to confirm the location of the fault. The LWD tool has given us the first glimpse into the subsurface and the plate boundary interface.

The science team devours the 5m long print out showing the newly available LWD data.

Record Start2012年04月24日

Three weeks into the expedition and we were still waiting for the drilling to begin. There had been several false starts during the last two weeks and everyone was getting anxious about the delays. April 22 was a Sunday so there were fewer work activities as the science party relaxed on the weekend. It was also my birthday. I was completely surprised when the scheduled afternoon coffee break turned out to be a birthday party for me.

A lot of effort had gone into decorating the lounge for the party. I’m sure people had more fun creating all the elaborate designs, than the actual party itself. That’s fine with me since I favor any reason to have some fun. Among the decorations, there was a megathrust/sea cucumber/methane molecule/catfish sculpture, a big rainbow poster signed by everyone, leis made of paper flowers, and lots of balloons with written messages. I especially liked the balloon which promised a birthday present of ‘Data’.

Christine Regalla with the ‘Data’ balloon from the birthday party.

The ship’s cook provided a cake and Louise Anderson told me to make a secret wish and blow out the candles (3 lighters held by Sanny Saito, Virginia Toy and Nobu Eguchi). Although, everybody knew that my wish was for the success of the expedition and especially to start collecting some data.

Data !

Needless to say, I am writing this blog because the birthday wish came true. If it hadn’t come true, I would be talking about albatrosses and poetry. A little before midnight we got the word that the drill bit was close to the ocean floor and we were ready to ‘spud in’ (another message on a party balloon).

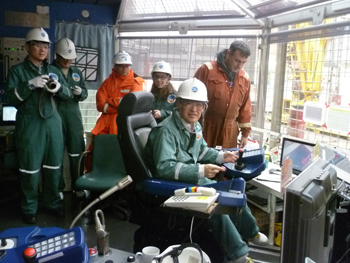

One responsibility of the co-chiefs is to verify that the ship is in the correct location to start the borehole. Fred Chester and I went to the control room on the rig floor to give the approval for drilling, not that we really knew where in the ocean we were, other than having some GPS coordinates from the bridge.

Driller’s house where operations are controlled on the rig floor.

The start of drilling was rather anticlimactic and quite slow over the first few tens of meters. Although, it was a relief when we received confirmation that logging data were being received from tools on the drill string. It is impressive that signals from the instruments near the drill bit can be sent through 7 kilometers of mud and water by acoustic pulses. This telemetry system had never been used before over such a long distance.

We were collecting data! A long three weeks of mostly waiting onboard the ship and an even longer year’s work by so many people in preparation for the JFAST project, and now the first borehole was really started and we were on out way to the fault !

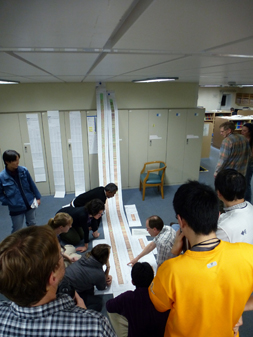

Monica Wolfson in front of monitor which displays logging data. 7079 m is the record breaking depth, as recorded at the rig floor, which 28.5 m above the sea level.

New World Record

Not only did we start collecting data for Expedition 343, we also set a new record in the process. Around 8:30 the next morning, Monica Wolfson, a morning shift watchdog, came by to say that the drilling was approaching the eagerly anticipated depth of 7049.5 meters below the sea surface. This depth represented the previous greatest total depth below sea level for any scientific ocean drilling project, and we were about to break that record. Colored data points appeared on the logging monitor, indicating that the drill bit was passing 7049.5 meters. Jim Sample popped open a precious can of Coke and carefully portioned it out into 15 small paper cups for a toast to the historic occasion.

Drilling continued through the night to a depth of 7308 meters below the sea surface (424 meters below the seafloor with a water depth of 6883.54 meters). Previously, the deepest penetration below the sea surface, as mentioned above, was 7049.5 meters during Deep Sea Drilling Program (DSDP) Leg 60 to the Marianas Trench in 1978. The DSDP borehole was drilled 15.5 meters below the seafloor in a water depth of 7034 meters.

From a birthday party to a wished for data collection, and from a long anticipated drilling start to a new world record, it was a couple of exciting days on the D/V Chikyu.

Breaking the depth record for scientific drilling.

第2話 「地震の大きさ」は重要ではない?!2012年04月20日

ちきゅうレポート<番外編>第1話に引き続き、本航海の共同首席研究者、京都大学のモリ・ジェームズ・ジロウ教授に船上でお話を伺いました。

-ところで、ジムさんは、いまおいくつですか?

えーとね、55歳です。来週4月22日で56歳だよ。(一同:あらら、船上で誕生日、Happy Birthdayをやらなきゃだね。)生まれはアメリカのシカゴの近くの町です。ワタシはね、(見た目は日本人ですけど)両親もアメリカ生まれの日系三世です。ワタシのおじいさんが、100年前にアメリカに渡りました。

-おじいさんの出身は?

初日の航海日報を読んだ?「ちきゅう」は千葉の勝浦沖を回航してきたって報告したんだけど、その勝浦出身です。おじいさんについては、子供のころからいろんなエピソードを聞きましたね。たとえば渡米した時、勝浦から横浜まで歩いて行って、そのまま単身で船に乗ったらしい、とか。1890年のことです(注:明治23年)。その当時にアメリカに渡るのは、ある意味冒険だったと思うよ。

-ジムさんは、やっぱり、子供のころから地学が好きだった?

いや、大学まではずっと物理を勉強していました。大学3年生の時に、夏にコロンビア大学ラモント・ドハティ地球物理研究所というところにインターンシップに行ってね。そこが本当におもしろかった。研究者が世界中を飛び回っていてね。これはイイと思ったよ(笑)

「アラスカの火山にも、ヘリコプターで地震観測に出かけたよ」(右がジムさん)

写真提供:James Mori

それで大学を卒業したら、そのままコロンビア大学の大学院に進み、そこで初めて地震学を学び始めました。何がイイって、地球科学は、何が起きているのかを自分の目で見ることができるってこと。物理は本当に何も見えないからね。ワタシにはそこが面白かったです。

NOAA(米国大気海洋庁)のヘリコプターに乗り込んで、アラスカの火山にも観測に出かけました。エマージョンスーツを着てね。あと必ず猟銃を持ってね、グリズリーが出てくるから。でも天気が悪い時はヘリコプターが高い山まで行けないので、釣りばっかりしてた(笑)。そう、キングサーモン。とにかく、地震の観測のために、人が全く行かないようなフィールドに行けることが分かって、研究にのめりこみました。

「地震」と「人間」との関係

-ところで、これまでどんなところで観測を行ってきたのですか?

大学院を卒業して、最初の就職はパプアニューギニア国立のラバウル火山観測所でした。実は、1983年からこの地域の地震が増えてきて、そのうち大きな噴火が起きると予想されていました。そこで、パプアニューギニアの研究所は、地震学者をずっと探していました。というのも、実は前任者が観測中に噴火に巻き込まれて亡くなってしまったので。

でも、なかなか後任者が見つからなくてね。誰も行きたがらなかったから。そこで、ワタシが行くと言ったときに、みんなビックリしてね。どうして決して生活環境も良いとは言えず、しかもあんな危険なところに行くのかと。

ラバウルの街のマーケットでいつも野菜とかを買っていたよ

写真提供:James Mori

-それでも、なぜ行こうと思ったの?

んー、実は特に理由はないんです(笑)。もちろん心配はあったけど、行ってみようかと。実はあの時は結婚したばかりでね。新婚で最初に奥さんと一緒に暮らしたのがパプアニューギニアでした。あそこで3年間暮らしたんだけど、噴火や地殻変動が多かったですね。国立の研究所だったので、パプアニューギニア全国を観測していたんだけど、3年間に4つの火山が噴火して、マグニチュード7の地震も3回も起きました。

噴火前のパプアニューギニア・ラバウルの街並み。

いまは大噴火により街はすべて消えてしまいました 写真提供:James Mori

火山は、地震が起きる場所や周期、回数などの変化を丁寧に観測していけば、どのくらいで噴火しそうか、ある程度の予想はつきました。結局、94年にラバウル火山が大噴火して、ワタシが暮らしたきれいな街も全部なくなってしまいました。

-その後、カリフォルニアのアメリカ地質調査所(USGS)に移ったんだよね?

そう。そこで私の仕事内容も全く変わりました。パプアニューギニアは、地震が多いが比較的に人口が少なかった。一方で、同じように地震が多いが、カリフォルニアの大都市には何千万人という人が暮らしている。そういう、たくさん人が住んでいる中で地震というものを考えていかなければならない。同じ地震の研究でも、人との関係性が全く違っていました。

92年に南カリフォルニアで発生したランダース地震。

大きな断層が走っているのが見えるが、砂漠のど真ん中で発生したため、

被害が少なかった。その2年後にノースリッジ地震が発生。

写真提供:James Mori

パプアニューギニアでも、地震や火山を研究し、噴火しそうだとわかると警報を出すんだけど、人口が比較的少ないから街ごと避難することができました。暖かい気候だから家も木や草でできていたからね、地震で崩れたとしても、それほど危なくなかった。大噴火の時は、数万人が街ごと事前に避難しました。平常時に避難計画を立てたり訓練をしたり、よくやっていましたよ。それがすごく活かされたと思います。

一方のカリフォルニアは、全く違う環境でね。高層ビルは建っているし、人口もものすごく多い。このカリフォルニアの新しい職場では、メディアを通じて世の中にどんな地震であったかを伝える役割もありました。日本の気象庁のように、発生した地震がどんな地震だったとか、こんな災害に気を付けて、とかをアメリカの市民に向けて発表していました。

94年に起きたカリフォルニアのノースリッジ地震の時、ワタシは地質調査所でこの地域を担当する責任者でした。実は、このノースリッジ地震は、地震の規模(マグニチュード6~7)に比べて被害が甚大だったという点で、神戸の地震とすごく似ていたと思っています。(ちなみに、偶然にもどちらも1月17日に起きました)

あの時に、各国からカリフォルニアの地震被害を視察しにやって来てね。日本からもやって来てワタシが被災状況を案内しましたが、崩れ落ちたハイウェイを見て、あんなことは日本では起きない、日本はしっかりと作っているから絶対に落ちないよ、と言われたことを覚えています。でも実際には、その1年後に神戸で同じことが起きてしまいました。

この時に、日本でも、アメリカでも、研究の方向がすごく変わったと思います。地震という自然現象をただ研究するだけではなく、観測のネットワークを作るとか、想定マップを作成するとか。日本では緊急地震速報の整備も始まり、研究者が持っていた情報を積極的に発表するようになってきました。

-緊急地震速報に関心があると聞きましたが?

そうだね。カリフォルニアの地震も、神戸の地震も、どんな規模の地震であったのかがすぐに正確に分からず、発生後に少し混乱もありました。これが残念だったとワタシは思っています。地震の大きさが基準となって緊急時の対応も違っていましたからね。初動がね、大事だから。

以前に、大地に見渡す限りに断層が走り、何mも隆起したような地震を調査したのですが、そこは砂漠のど真ん中だったので、あまり被害がなかった。地震があったことすら、なんだかみんな他人事のようだったね。こういう経験ですごく感じたことは、「地震の大きさ」が重要ではなく、「人に関わる地震」が重要であるってことです。

あとはね。余談だけど、フィリピンのピナツボ火山が大噴火した時にも調査に行っていてね。実は、危ないところだった。火砕流に巻き込まれそうになって。あと数百mのところまで火砕流が来てね。ほんと、あの時は危なかったよ。そのあとの地面は数か月間も熱かったね。

私は、地震や火山などを通じて地球の動きを研究してきました。災害に直結するような変動がなぜ起きたのかを研究者として調べ、リーズナブルな理解をし、それをみなさんに説明しなければならないと考えています。

本航海の共同首席研究者のモリ教授は、じつは若い時から冒険の連続だったのですね。「ちきゅう」に乗り込もうという気持ちも奥底を感じることができました。では、なぜいまモリ教授たち研究チームは「ちきゅう」に乗り込み、ここ日本海溝までやってきたのでしょうか。そのインタビューは、ナショナル・ジオグラフィック誌オンライン版「Webナショジオ」でただいま連載中の「深海7000メートル!東日本大震災の震源断層掘削をミタ!」でもご紹介しています。

(番外編は、まだまだつづく?)

第1話 「いってきます」2012年04月17日

わたしはいま、仙台市から東へ250kmの場所の太平洋の上です。見わたす限りの水平線が広がっていて、もちろん陸地なんか、な~んにも見えません。ポツーン、と大海原にいます。

4月1日に清水港を出港した地球深部探査船「ちきゅう」は、一路、日本海溝を目指して航海してきました。毎回、出航というイベントでは、これから旅立つ人も、見送る人も、なんとなく感傷的な気持ちになるものです。

これからしばらくの間、家族や友人、恋人と離れ、しかも厳しいと分かっている仕事に向かうという心境は、文字通りに期待と不安が入り混じった複雑なものです。

4月1日に雄大な富士に見送られながら旅立ちました

写真提供:JAMSTEC/IODP

特に船長から指示があるわけでもないのに、出航の時間が近づくと、何となく各自がデッキに顔をだし、陸で見送ってくれる仲間や、わざわざ港まで見送りに来てくれたのに名前も存じ上げないみなさんに「ありがとう!いってくるよっ!」と、見えなくなるまで一生懸命に手をふりました(撮影中だったので心の中だけですけど。)わたしの隣にいたエンジニアの山崎クンとも、がんばろうなー、とお互いを励まし合うような妙な連帯感が、この瞬間からジワリジワリと湧き出してきます。

見送る人に「ちきゅう」のヘリデッキから手を振る科学者たち

写真提供:JAMSTEC/IODP

さて、いまわたしたちは、日本海溝という海底から、はるか7000m上方に浮かんでいます。「海溝」というのは、地球を覆っているプレートと呼ばれる分厚い岩盤が、ゆっくりと、でも着実に地球の奥底まで沈み込んでいく入口です。今では地球のあちこちに海溝があるのが分かっています。日本の西側ではフィリピン海プレートというヤツが動いているし、ここ日本海溝でも、太平洋プレートというヤツが年に約10cmの速さで動いています。そう、地球は動いています。

7000m↓の世界

さて、出航から2日後の4月3日朝8時に「ちきゅう」は調査海域に到着しました。ここには、海以外に何もありません。街も学校もありません。いま、わたしの足もとの青黒い海には、ただただ、その底まで7000mもの水があります。

深さ7000mの水。これはもう、圧倒的な量です。私は仕事柄、「ちきゅう」は大きい船だよ~、と小学校で授業をしたりするのですが、もう本船の小さいこと小さいこと。公園の池を見たアリのような気持ちです。なんだか暗く深い海の底に吸い込まれそうな気持ちにもなってきます。地球は水の惑星だということが、文字としてではなく、五感を通じて頭に刻まれます。

圧倒的な量の水をたたえる惑星に生きているんだと実感中

写真提供:JAMSTEC/IODP

その日本海溝の海底というのは、どんな世界なのでしょうか。実は、いま7000mまで潜航できる探査機は世界にほとんどありません。(JAMSTECの「かいこう7000Ⅱ」がそのひとつ。)ということは逆に、そんな世界のことなど、ほとんどわかっていないんだと言った方が正しいのだろうと、わたしは思っています。

海って言われると、海水浴、サーフィン、海の家、花火、あー青春、とか、わたしがイメージできるのは、これまで自分が見て触れたことのある情景がほとんどだということに気づきます。自分が知っていることだけで全てを理解したつもりになること。海に限らず思い当たる節もあり、反省するばかりです。

さて、そんな超深海の世界は、ものすごい圧力の世界です。宇宙空間とは逆に、深海には巨大な力がかかっています。たとえば、これから「ちきゅう」が掘削しようとしている海底では、みなさんの人差し指の先っぽ、その先に体重700kgの小人がニッコリと仁王立ちしているという計算になります。

もう一つ、実はすごく「遠い」ということです。7000mというのは7kmです(当たり前)。通勤距離が7kmだとすると、まあまあ楽な方だよね~、と言えるかもしれませんが、これを立ててみるとどうでしょうか。自分の家から7km↓。もうそこは未知の世界です。7km↑はなんとなく想像ができます、もっと高く飛行機は飛んでいますし。でも7km↓は見えません。暗いです。狭いです(たぶん)。

そんな↓の世界まで、太さ20cmばかりのドリルで調べようというのです。あー、あまりにも無謀、あまりにも弱小、と思いますよね。出航時のわたしの心細さを少し共感できたでしょうか。

さてようやく主役登場ですが・・・

今回の研究ミッションは、世界最強と呼ばれている(ような気もする)科学探査船「ちきゅう」にとって、実はひっじょーにチャレンジングな航海です。どんだけ厳しい戦いに漢(おとこ)たちが挑んでいるのかは、またいつかご紹介するとして、そういう研究をするぞー!と、先頭に立ってわたしたちのお尻をぺんぺん叩いているのが、共同首席研究者のモリ・ジェームズ・ジロウさんです。

この方、とっても気さくな人で、わたしもつい、「ジムさん、ジムさん」と気軽に声をかけてしまうのですが、実は京都大学防災研究所の教授です。こわっぱなわたしからしたら、ずいぶんとえらい方なのです。でもなんとなく、その人柄のフランクさや、英語での会話に甘えてしまって、「おいジム、調子はどうだい?」な~んて、テキサスのカウボーイのようなため口をきいてしまうのです。

ドリラーの操縦席に座り、ちょっと童心に帰ったジムさん

写真提供:Sanny Saito for JAMSTEC/IODP

さて、そんなモリ教授に、なぜ「ちきゅう」が持てる限りの力を出し切っても、ようやく達成できるかもしれない、という厳しい調査に挑むのか、お話を伺いました。

といったところで、続きはまた次回!になってしまったようです。ではでは!

(つづく)

Why are there field geologists on a drilling vessel?2012年04月16日

このレポートは、Scientific American誌ブログにも掲載されています。

Greetings from Drilling Vessel (D/V) Chikyu, currently maintaining position about 220 km east of Sendai, directly over the Japan Trench and above the fault area of the March 11, 2011 Mw9.0 earthquake. We are on International Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Expedition 343: the Japan Trench Fast Drilling Project (JFAST). Our goal here is to drill into the seafloor and penetrate the earthquake rupture zone at around 1-km depth.

We will make direct observations and collect samples of the fault zone below the seafloor, in order to understand the very unique features of the earthquake last year, to clarify how the rupture propagated all the way to the trench and generated such a great tsunami, and to learn more about the general physical properties that control earthquake rupture which we can apply to other areas.

The speed with which this expedition has been executed by international cooperation is unprecedented (it usually takes ~3 years to plan a research cruise), because some of the phenomena we are trying to observe, which record the details of the earthquake slip process, are literally fading away into the sea. I’ll discuss these in a future post. I’ll start with something a little more concrete: the rock samples we hope to collect by drilling directly into the plate boundary fault which generated the earthquake.

A little background about the geology of earthquakes

In the shallow parts of the Earth’s crust, rocks are strong. As you look deeper in the crust, temperature increases, and when it reaches about 350-450°C, most rocks soften and start to gently flow. So, earthquakes and other types of brittle failure occur most often at shallower levels. At the surface, stress is too low to initiate earthquakes, but as you go down, the stress from the overburden load and from tectonic plate motions both increase.

These two constraints are the boundaries of the “seismogenic zone” ? where earthquakes nucleate and where the most earthquake energy is usually released. The actual depth limits on the seismogenic zone vary from plate to plate and fault to fault ? depending on the specific rock type and temperature profile of the crust, and the local conditions of stress and rate of plate motion.

In my usual research, I go around the world looking for rocks from ancient faults, specifically, inactive faults that have been uplifted 10 or 20 km, the overburden eroded away, to expose the inner workings of the seismogenic zone. I go to the places where I can see the most rocks: deserts, where there is little soil or vegetation cover, and in wetter climates, I seek out ancient faults in glaciated or uplifted terranes where erosion has been rapid enough to expose the rock. Here’s one of the places I have worked, a cliff on the beach on Kodiak Island, Alaska:

That’s geologist Francesca Meneghini from Pisa, Italy, wearing the bright orange rain gear. Francesca and I were in Alaska (with Casey Moore, another JFAST geologist) to map the sandstones, shales and volcanic rock that were deposited in an ocean trench 60 million years ago, similar to the Japan Trench today.

These sediments were sheared during subduction in the boundary between two tectonic plates. This thrust fault shook with great earthquakes and produced tsunamis. And now, 60 million years later, uplift and erosion has exposed the core of the former earthquake generation zone in these cliffs where we can see it. As field geologists, we have the great opportunity to observe the inner workings of faults, on the scales that are really important; most earthquakes come from thin (1-10 cm) faults within zones about 10-30 m wide. It’s really like we are visiting earthquakes where they live.

But ? we also have the disadvantage of studying faults so ancient that we have no idea exactly how big the earthquakes were, or how frequent ? it can be hard to link our observations of earthquakes that occurred millions of years ago to the real-time events on modern faults that affect people’s lives.

The JFAST Expedition has the opposite situation: the team sailing on D/V Chikyu right now are very aware of the human experience in the earthquake and tsunami of last year. The vessel herself survived the tsunami in the harbor at Hachinohe, north of Sendai, and many of our colleagues on board experienced the earthquake and tsunami first-hand.

Investigating the geologic processes takes on a very personal aspect, and the desire to understand these events is more than just academic. In this case, we know the exact timing of events and the scale of fault slip, but the fault lies 8 km under the ocean’s surface. The water at our chosen drill site is 6910 m deep, and we think the fault is a bit less than 1 km below the sea floor. This site was chosen to stay within the drilling capabilities of D/V Chikyu ? if we went farther west, the water would be shallower but the fault would lie deeper below the sea floor, and east, the water would be too deep.

If successful, we will complete the deepest hole ever drilled in comparable ocean depths. This is an extraordinary effort to gain access to an active fault. Other earthquakes have been the focus of subsurface investigations, with rapid response drilling in Japan after the Kobe earthquake (1995), and in China after the M7.9 Wenchuan earthquake (2008). These efforts have revealed a lot of new information (and new questions) about the inner workings of the earthquake cycle, but these faults are quite different than the subduction thrust faults that are responsible for the greatest earthquakes and most of the tsunamis.

Drilling is the only way to see this fault, but this kind of view presents its own challenges

If we are successful in recovering a core sample from our drilling efforts, we will get a 6.5-cm diameter core, up to 400 m in total length, and somewhere in this long noodle of mud and rock we may have a tiny slice of the March 11, 2011 earthquake fault.

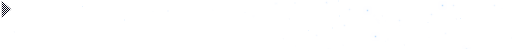

This second picture shows our geological map, in color, of the sea cliff in the first photo. Subduction faults are complicated mixtures of rock. The red dashed line shows the thin faults where earthquakes struck 60 million years ago. To give you an idea of the challenges we will face on Chikyu, I’ve made up two different hypothetical boreholes to show you what it might be like if we were studying this ancient fault zone in a thin drill core. Next to each “core section” you can see the layers of rock, cut by faults, which a geologist might read and record from the core.

We will only have one core of rock, one tiny window, into what we know will be a complicated zone. We won’t know whether the hole we’ve drilled penetrated a more complex location, like core 1, or a simple section, like core 2. We may see only one major fault, as in core 2, or we may see multiple faults, preserving a record of additional, older earthquakes. In either case, we will be able to answer some important questions: How thick is the zone that slips during an earthquake? How hot does it get? And what characteristics do these rocks have that make them especially prone to extreme earthquake slip?

The field geologists on board will be leveraging our insights from field studies of exposed faults to try to make sense of our core sample, and the measurements we make of the borehole walls while we are drilling. Unlike my studies of ancient fault outcrops, this time we will also measure the heat and chemistry in the fault that only last a few years after the quake. So if we find a record of many old earthquakes in our core, and I hope we do, we will be able to use this information to pinpoint the specific one that slipped on March 11, 2011.

この2週間、いろいろありました2012年04月16日

出航からこの2週間、船上には嵐が来たり、機器の調整が続いたりといろいろありましたが、今日の夕方(4/13 金曜日!)やっと最初の掘削工程となる、20インチケーシングの海中への降下が始まりました。

20インチケーシングパイプを海底まで運ぶランニングツール

ふぅ、やっとスタートラインについた!という心境です。

荒天に揺られた数日、その後のこう着状態。乗船している研究者の顔も日増しに厳しくなって来ていた、このところでした。

ドリルフロアではエンジニアやドリラーの人々は必死に働いています。もちろん研究者達はその働きをリスペクトしています。もちろんリスペクトしていますが、研究チームのサポートを統括する私としては、はやくデータが見たい、サンプルを採りたい!と気がはやる研究者たちの心の中で、なかなか簡単に物事が進まない現実に対する欲求不満がつのってくるのが肌で感じられるこのところでした。

風速40m/s近い嵐もやってきたりと。

毎朝の全体研究会議でオペレーションの進捗状況を報告するのが、日に日に辛くなる毎日。でも私が笑顔を忘れたらダメなんだと、なんとかみんなを笑わせて・・・と四苦八苦。

もちろん、この先にもいろいろな事が待ち構えているはずです。ひとつひとつそれを越えてゴールを目指す、まぁそれが航海の醍醐味かな?と言えるのも、とりあえずスタートラインに立てたからですね。

毎朝のジョークを考えるのが日課

Frictional Heat2012年04月13日

Chikyu crew testing out frictional heating (courtesy of Charna)

One of the major objectives of JFAST is the measurement of temperature in the fault zone. Why is this important - well, rapidly rub your hands together like the some of the Chikyu crew are doing in the above picture. Your hands start to get warm due to friction. The slip that occurred on the fault during the Tohoku earthquake would have produced a lot of frictional heat. By measuring how the temperature of the fault zone changes with time scientists can estimate the frictional heat produced when the fault slipped. This can then be used to infer information about frictional stress on the fault.

Short update from onboard Chikyu2012年04月13日

Chikyu has been on site of our proposed boreholes for a few days now, but we haven’t yet begun drilling because various pieces of gear are playing up ? I don’t think this is atypical on drilling operations and am happy to bide my time and hope it all works out and we begin to core soon.

In the meantime, through variable weather, I’ve been learning my way around the ship, and learning about ship-board life.

The sun is reflected off a calmer ocean than today! Notice the slight curve in the horizon?

Photo by Nobu Eguchi.

One thing that keeps striking me is the apparent endlessness of the ocean we are sitting upon. I’ve been really enjoying standing on deck observing it. Every time I go up there, the sea state seems to have changed. Today it is particularly ‘interesting’ since there are two major conflicting sets of waves that are interacting. One large set coming from the east appear as ridges stretching across the whole ocean. A second set are less continuous, but when they intersect the large set in the right way, they form breaking waves and foaming masses of white water. When these hit the ship, we feel massive shudders, much like earthquake shaking. This just seems really odd in light of the two very large (Mw 8.2 and 8.6) strike slip earthquakes felt off Sumatra last night. Jim Mori (Co-chief scientist of this expedition) just gave an interesting presentation on those earthquakes, and we discussed whether similar events could be felt in this region some time after the mega-thrust earthquake.

There have been so many great scientific discussions onboard over the last few days, about a wide variety of research the Science Party members are presently engaged in that is relevant to understanding this particular subduction thrust fault. I think we are all intellectually primed and really ready to start coring as soon as we can!

Christie Rowe (Canada) and Monica Wolfson (USA) try to illustrate the extent of the endless ocean from the relative safety of the helicopter deck.

Earning My Sea Legs2012年04月13日

Today marks the end of my journey on Chikyu. As a land lover, I wasn’t sure what to expect when I boarded (or even if the motion sickness medicine would work). I leave now surprised at how fast the time has passed and amazed at the brilliant scientists and crew working to make the expedition a success.

I was on Chikyu to assist with expedition-related education and outreach activities. Upon arriving, we were immediately given a crash course about life on a ship ? from meal times to evacuation procedures. We were assigned rooms and safety gear, and laboratory training started soon after. In no time, the science party ? composed of scientists from 10 countries ? started getting to know each other and sharing their excitement and thoughts about the work ahead.

The science party is only part of the Chikyu story. The ship operates with an impressive crew of about 150 people that includes everyone from roughnecks on the drill floor to cooks in the galley. The crew has been extremely kind and generous, making everyone feel at home. Dennis keeps us safe, Alex found the perfect safety goggles to fit over my glasses, and Romeo prepares delicious meals. During the typhoon-like storm last week, I was stuck in bed (the meds can only do so much), and to my surprise the crew left fresh towels by my door for when I was feeling vertical again.

I’m a bit disappointed to leave the expedition now, just as the activity is really getting started, but I’m looking forward to hearing more about the rest of the JFAST journey.