Episode. 1

10.27.2025

Blog 3

Smile! You’re on Candid Camera!

(Produced by Jose Cuevas)

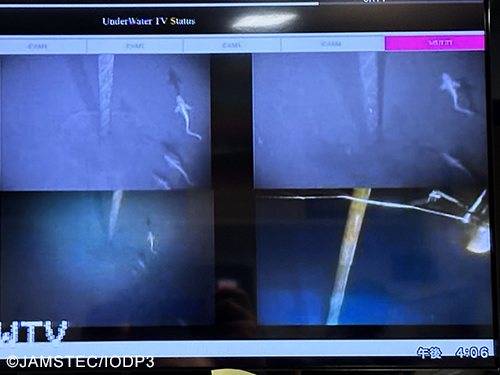

Operations have been progressing well, and as usual, we have our Underwater TV deep in the water to help us observe what is happening 7 km under the sea, closer to our drill hole. And it looks like our field site has some visitors!

These fish are likely rough abyssal grenadier (Coryphaenoides yaquinae). Their accepted range is in the abyssopelagic zone of the ocean, between 4 and 6 km deep, but there have been other recorded observations of this species in the hadal zone (deeper than 6 km) like in the Japan and Mariana Trenches. As it happens, we are operating in the Japan Trench, which helps with identification here.

Grenadiers get one of their common names from their prominent pointed dorsal fins, which resemble the mitre headgear worn by 17th century French grenadier soldiers (which also appears in ecclesiastical and chess settings as the headgear of bishops). They are also referred to as rat-tail fish, due to their long, slender tails.

These fish are generally benthic, living close to the seafloor, and have well-developed lateral lines which allows them to sense minute differences in pressure. This adaptation makes them highly sensitive to vibrations in the sea which can help them find prey. Their large eyes also help them, allowing them to take in more light.

While biology is not the focus of this expedition, working in the deep ocean means that sometimes we will encounter its denizens. While they may appear spooky and macabre to those of us who live on the surface, that simply means they are well-adapted for their deep-sea lifestyles.

Sources:

https://www.fishbase.se/summary/Coryphaenoides-yaquinae.html

https://archive.imascientist.org.uk/cryptic25-zone/question/how-did-the-fish-come-to-be-named-grenadier/index.html

https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/sN0y146pTmOEqE8zDUvj6A

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/the-fishes-of-the-deep-sea.html

https://www.britannica.com/animal/deep-sea-fish

10.24.2025

Blog 2

Looking Sharp and Staying Safe

(Produced by Jose Cuevas)

There is never a dull moment aboard D/V Chikyū. For most of Expedition 502E, we have been running on 24-hour operations, which means sometimes the science must visit the drill floor in the early hours of the morning, or the exceptionally late hours of the evening.

And a heavily industrialized ship like Chikyū takes safety very seriously, so whenever we observe operations on the drill floor, we need to fully suit up in personal protective equipment (PPE).

The PPE we wear on the drill floor serves an important purpose: it is meant to keep people safe! On the drill floor, we wear coveralls, safety boats, safety glasses, gloves, and a hard hat. The crew who work there for hours at a time also use hearing protection for the continuous noise. These pieces of equipment are meant to protect us from hazards we may encounter working in close quarters with heavy machinery and environmental exposure. That said, PPE is very situation-dependent: the PPE that protects you while operating a crane might not be appropriate or even safe when you are working with other equipment, like a fume hood!

In science labs ashore and on the Chikyū, PPE might alternatively look like a lab coat with rubber gloves and safety glasses. This gear contributes to the popular perception of what a scientist’s “uniform” is but is meant to keep scientists safe while running laboratory experiments! No matter what we are doing on the Chikyū, one of our most important goals is to keep everyone safe!

10.22.2025

Blog 1

The Language of Sailing

(Produced by Jose Cuevas)

People often say that sailing ships have their own language. It’s true: the ship’s left and right become port and starboard. I’ve sailed on a handful of research expeditions before, so I’m used to nautical words, but this is my first time on a Japanese ship (and my first time in Japan!), so I was excited to experience Japanese culture, language, and cuisine.

And with an international crew, that’s not the only thing I hear. Conversations in Japanese echo across the bulkheads, sure, and the official language of the operations aboard is English. But one of the beautiful things about D/V Chikyū is how she is a vessel for international collaboration. Scientists and crew members come from all over the world to learn the secrets of the rocks below us, and Japanese and English are both used for communications. In addition to Japanese and English, I’ve also heard Tagalog and French. I am certain that expeditions with larger science parties have more languages with them, as well!

This is the most I’ve heard or spoken Tagalog since my last visit with family. It’s refreshing to be able to hear my mother tongue, and to be part of a community of Filipino sailors who have taken to the sea. I took French in high school and at university. It’s rusty, but I will try (j’essaie) my best use words or phrases to better converse with Doriane, another science communicator. In both cases, languages help to create connections in our international collaboration.

There are so many languages around us. While port and starboard are both part of the language of sailing, so are babor at estribor, and of course, bâbord et tribord.

12.17.2024

Blog 6

(Created by Nur Schuba, one of Science Outreach Officers)

第9話: 「ちきゅう」でのお別れ

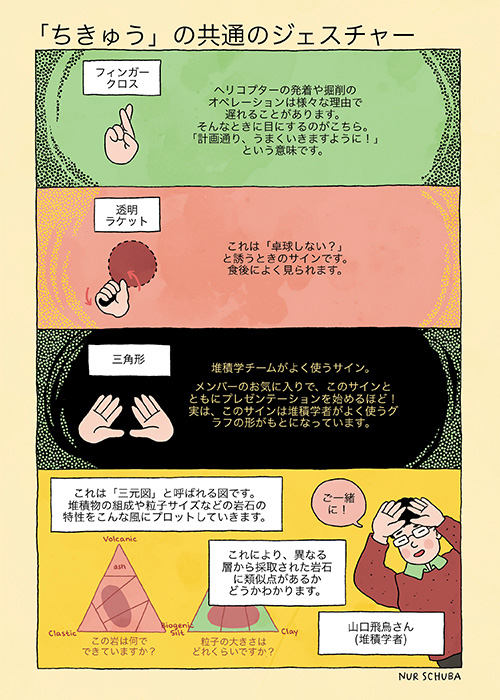

第8話: 「ちきゅう」の共通のジェスチャー

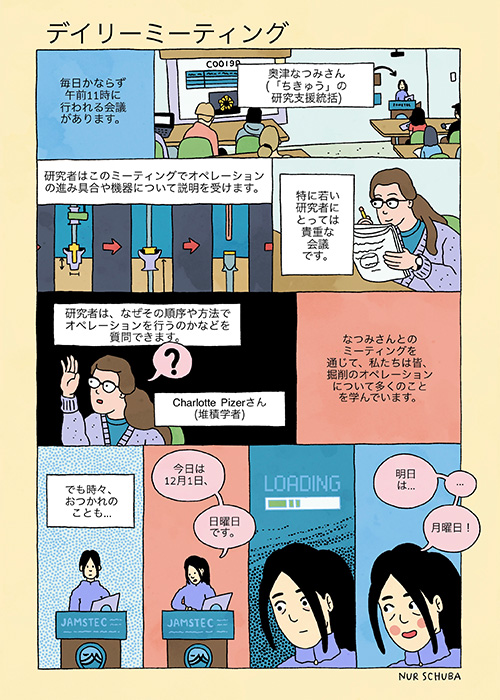

第7話: デイリーミーティング

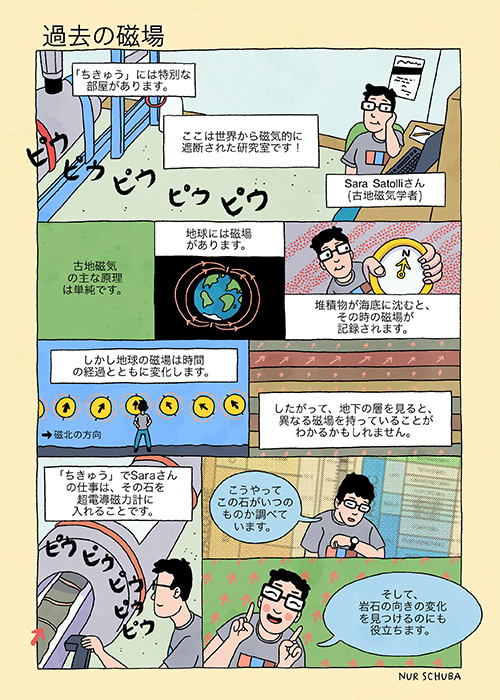

第6話: 過去の磁場

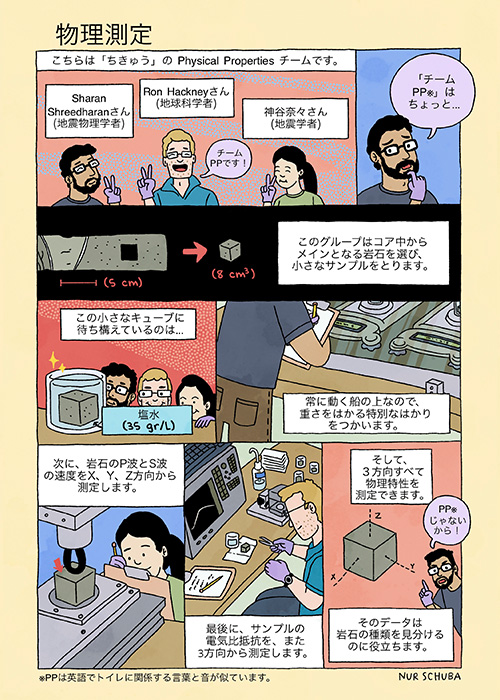

第5話: 岩石サンプルからデータをとるのは物理特性チームの仕事

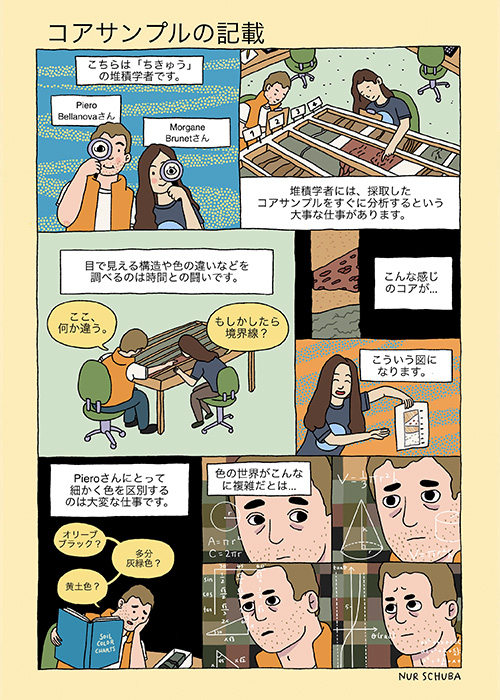

第4話: コアの記載は大仕事!

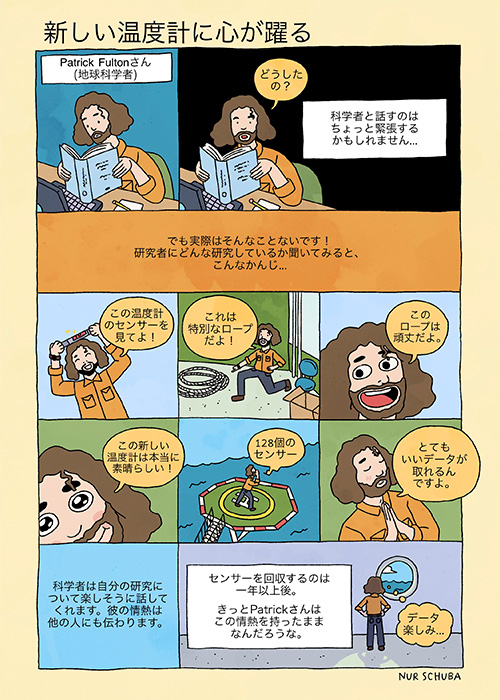

第3話: パトリックさんはこれから設置する温度計にとてもわくわくしてます。

第2話: 「ちきゅう」にはルールがいっぱい!

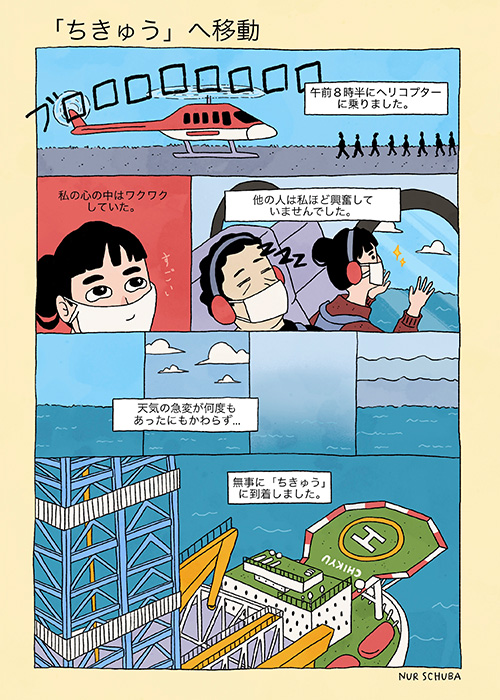

第1話: 「ちきゅう」への「通勤」はちょっと特別です。

11.21.2024

Blog 4

What_if ? - The JTRACK core observation+interpretation game.

(Produced by Callan Bentley)

Professor Callan Bentley in this video asks three IODP Expedition 405 scientists, Co-chief Dr. Christine Regalla (Northern Arizona University, USA), Dr. Catherine Ross (University of Colorado-Boulder, USA), and Dr. Amy Gough (Heriot-Watt University, UK), a series of "What If?" questions/scenarios about what different possible findings in the recovered core samples would tell us about the origin and subsequent history of the sediments they are created from.

11.20.2024

Blog 3

Cooking with Cameron TODAY'S RECIPE: SQUEEZE CAKE. (Produced by Callan Bentley)

Professor Callan Bentley and UCLA Graduate student Cameron Brown share a recipe from the geochemistry lab aboard Chikyu - "How to make a squeeze cake!"

11.19.2024

Blog 2

Reflecting on my two weeks aboard CHIKYU. (Produced by Callan Bentley)

Callan Bentley, Associate Professor of Geology at Piedmont Virginia Community College (PVCC, USA), describes his experience being aboard DV Chikyu during IODP Expedition 405, and compares and contrasts this experience with other research cruises he has been able to join.

10.21.2024

Blog 1

The longest noodle (Writer: Callan Bentley)

Stretching from Chikyu’s drilling derrick down deep into the seafloor is a very long assembly called the “drill string.” When I stand on Chikyu’s deck and gaze aft at the derrick, I see the drill string beneath a yellow mechanical assembly called the “top drive.” It’s the size of a city bus, but vertical. The top drive visibly bobs up and down relative to the derrick’s frame, as the ship compensates for the heaving motion of the ship. Below it, the drill string appears at first to be a simple black line, backlit by the sky. But when drilling is underway, you can see that it is rotating. White painted numbers appear on one edge, twist into view, and then slip around back.

Aching to unboggle my mind, I search for an analogy. The first thing to occur to me is a long-tailed ichneumon wasp. (Google it to be amazed, and perhaps horrified.) It has an ovipositor like a hypodermic syringe! But a living organism laying eggs isn’t a great match for what the Chikyu is doing here.

Then I consider pasta. Standard spaghetti noodles measure 25 cm long by 1.59 mm wide. The diameter of the Chikyu’s drill string is 13 cm wide, and as I mentioned, it’s 7.2 km long. So how long would I have to make a spaghetti noodle to get it to match the drill string of Chikyu? Dividing the drill string’s diameter by that of the noodle, I get a ratio of 81.8. Then I divided the length of the drill string by that ratio, and produced (in theory) a noodle 88 m long (288 feet), which is about four-fifths the length of a football field.

That’s some noodle!

Now let’s get the orientation right. Imagine taking a power drill, and fitting the upper tip of this prodigious noodle into its chuck. Now stand on the roof of a 25-storey building, lean over the edge, and use the spinning noodle to drill a tiny hole in the lawn in front of the building’s entrance. It’s outrageous to consider, yet that is pretty much what Chikyu is doing here in the western Pacific.

Now let’s get the orientation right. Imagine taking a power drill, and fitting the upper tip of this prodigious noodle into its chuck. Now stand on the roof of a 25-storey building, lean over the edge, and use the spinning noodle to drill a tiny hole in the lawn in front of the building’s entrance. It’s outrageous to consider, yet that is pretty much what Chikyu is doing here in the western Pacific.