Observational Research in the Arctic Ocean to date - Chapter I : Prologue

September 5, 2022

Takashi KIKUCHI,

Director, Inst. Arctic Climate and Environment Res., Research Inst.

Global Change/Group Leader,

International Observation Planning Group,

Project Office for Arctic Research Vessel (PARV)

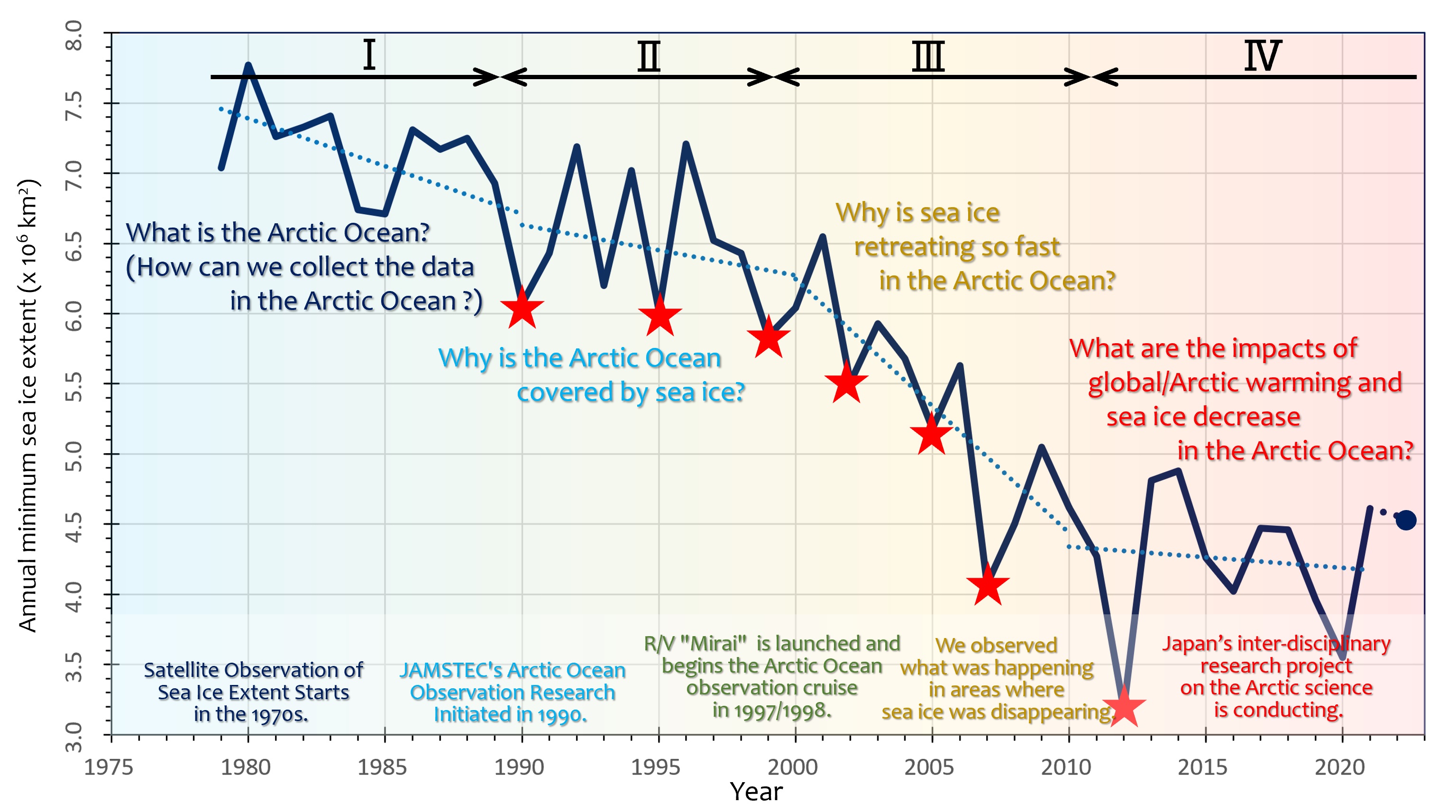

This article describes the history of Arctic Ocean observation and research to date, focusing mainly on the activities of Japan and JAMSTEC. Figure 1 shows the interannual variation of minimum sea ice extent in the Arctic Ocean revealed by satellite observation since 1979 with some comments about the purposes and activities of the Arctic Ocean observation. We divide the period from the start of satellite-based sea ice observations in the 1970s to the present into four periods and summarize the objectives and research activities conducted during each period.

I: Prologue (Expedition period before the beginning of satellite observations)

Before the 1970s, the Arctic Ocean as a whole was not yet understood as what the ocean and sea ice was like. Along with expeditions to the North Pole or other locations, scientific research was being conducted. The first means of transportation in the Arctic Ocean was on foot or by dog sled, but as technology developed, airships, submarines, and airplanes came into use. During the Cold War period after World War II, the Soviet Union, the United States, Canada, and other countries established bases on sea ice to conduct drifting observations and acquire data on and under sea ice in the Arctic Ocean. These observations have enabled us to obtain “point” and “line” data, and little by little we have come to know that the Arctic Ocean is covered with sea ice year-round and that the sea ice is drifting.

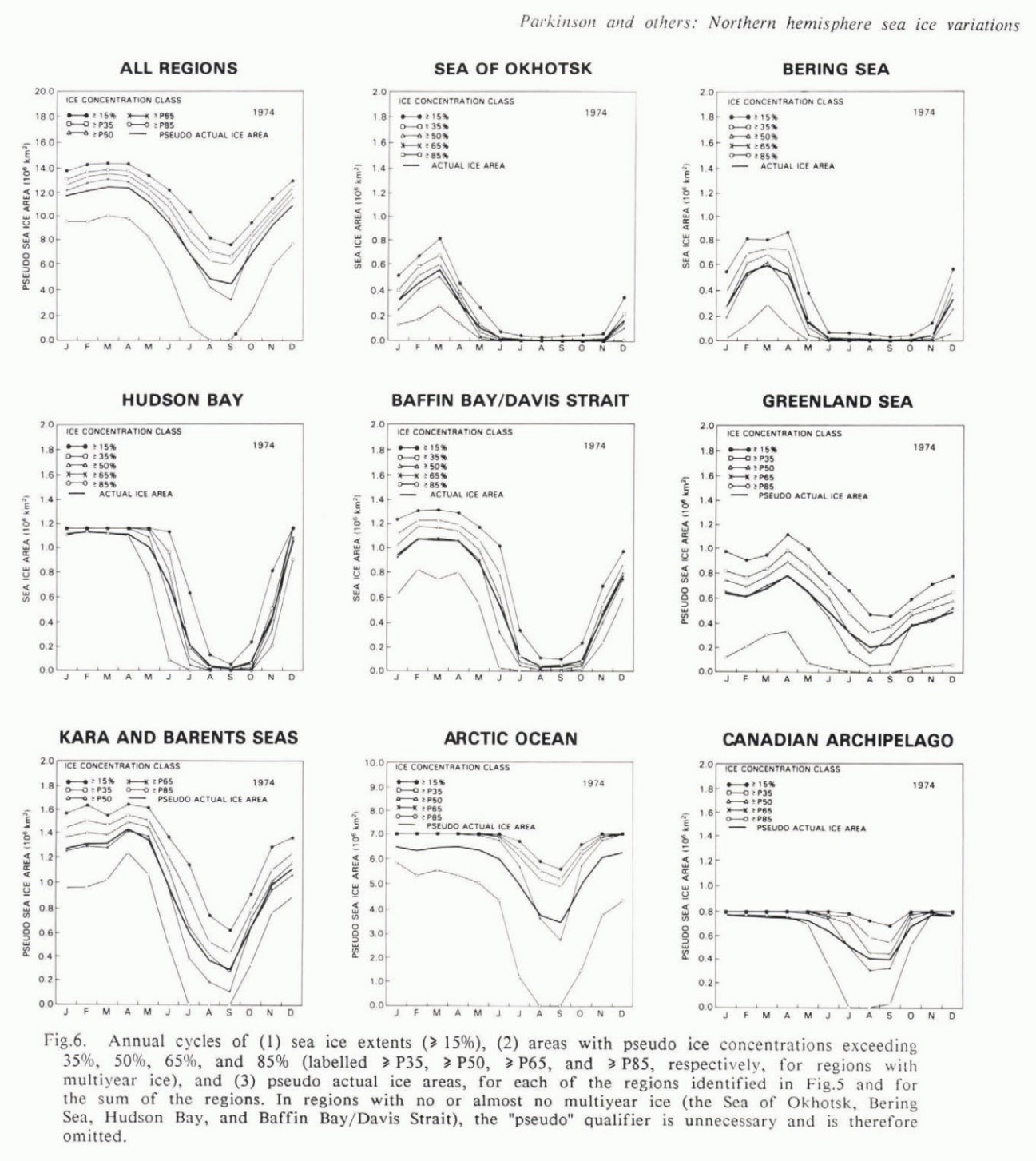

A major innovation in Arctic Ocean research came in the 1970s when satellite-based sea ice observations began. Satellite observation data, which had been used for atmospheric and meteorological observations since the mid-20th century, began to be used for sea ice observations in the polar regions in the early 1970s. In other words, monitoring sea ice conditions has become a priority for satellite observations. The brightness temperature data from the Nimbus 5 and 7 satellites, equipped with microwave radiometers that can capture the ground surface conditions even in the presence of clouds, provide daily information on the distribution of sea ice concentration in the Arctic and Antarctic. In other words, spatial-temporal changes of sea ice concentration could be seen not as "points" or "lines" but as " surfaces". For example, we found that the sea ice extent in the northern hemisphere in 1974 was maximum in March (~1.44 M km2) and minimum in September (~0.76 M km2). It was also quantitatively clarified that most areas of the Arctic Ocean were covered by sea ice all year round but surrounding seas (Hudson Bay, Baffin Bay, Greenland Sea, Barents Sea, Kara Sea, Bering Sea, and the Sea of Okhotsk) are free of sea ice in summer. Figure 2 shows the seasonal changes in sea ice extent in the Arctic Ocean and the surrounding seas (Parkinson et al., 1987b).

Sea ice observations using microwave radiometers continue now. Especially since 2002, data from Japanese satellites have been used around the world. Currently, observations by the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer2 (AMSR2) onboard the “SHIZUKU” satellite provide daily sea ice concentration data with a horizontal resolution of 15 km. This data has become an indispensable infrastructure not only for scientific understanding of the polar marine environment but also as basic data for future projections and as information that supports our daily life.

For the Japanese, the Arctic Ocean was a place of expeditions, like many others around the world. For example, there was impressive news in the 1970s that the Nihon University Arctic Expedition team reached the North Pole by dog sled (27 April) and that Naomi Uemura became the first person in the world to reach the North Pole by dog sled himself (30 April). In the 1980s, Japanese actress Masako Izumi attempted to reach the North Pole (abandoned in 1984, but succeeded in 1989), and adventurer Shinji Kazama reached the North Pole by motorcycle (1987).

Even though the Arctic Ocean was still considered an area for an expedition, Japanese researchers were collaborating with Arctic countries’ researchers on an individual and laboratory basis to conduct field observations and other activities. They conducted ocean and sea ice observation e.g., along the coast of Utqiaġvik (Barrow), Alaska, which is the northernmost point of the United States, as well as in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Hudson Bay, and Svalbard, Norway, to research snow, sea ice, and marine ecosystems. Hence we can call it a "prologue" to the start of Japan's Arctic Ocean research.

…..Continue to “Chapter II: Launching”

References

i. Parkinson, C. L., J. C. Comiso, H J. Zwally, D. J. Cavalieri, P. Gloersen, and W. J. Campbell (1987a). Arctic sea ice, 1973-176: satellite passive-microwave observations. Washington, DC, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA SP-489). P.299. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19870015437.

ii. Parkinson, C. L., J. C. Comiso, H J. Zwally, D. J. Cavalieri, P. Gloersen, and W. J. Campbell (1987b). Seasonal and regional variations of northern hemisphere sea ice as illustrated with satellite passive-microwave data for 1974. Annals of Glaciology, 9, 119-126, https://doi.org/10.3189/S0260305500000495.

iii. GCOM-W@EORC Homepage https://suzaku.eorc.jaxa.jp/GCOM_W/index_j.html (Refer on August 30, 2022)

iv. Editorial committee of JARE OB Club (2015). “Hokkyoku Dokuhon (Arctic Reader’s Guide)”, Seizann-do Shoten, ISBN978-4-425-94841-3 (in Japanese)

v. Holland, Clive (Translated by Masahide Ota) (2015). Arctic Exploration and Development c. 500 b.c. to 1915: An Encyclopedia. Doujidai-sha, ISBN978-4-88683-738-7 (in Japanese)