We’re in the midst of spring, and the cherry trees on the Yokohama campus are in full bloom, with some green leaves starting to sprout (see photo). According to the JMA, temperatures in eastern Japan were around average in March, while rainfall was a bit low (link to the Japanese website). In a few months, the heat of summer will descend upon us. So what is this year’s summer going to be like?

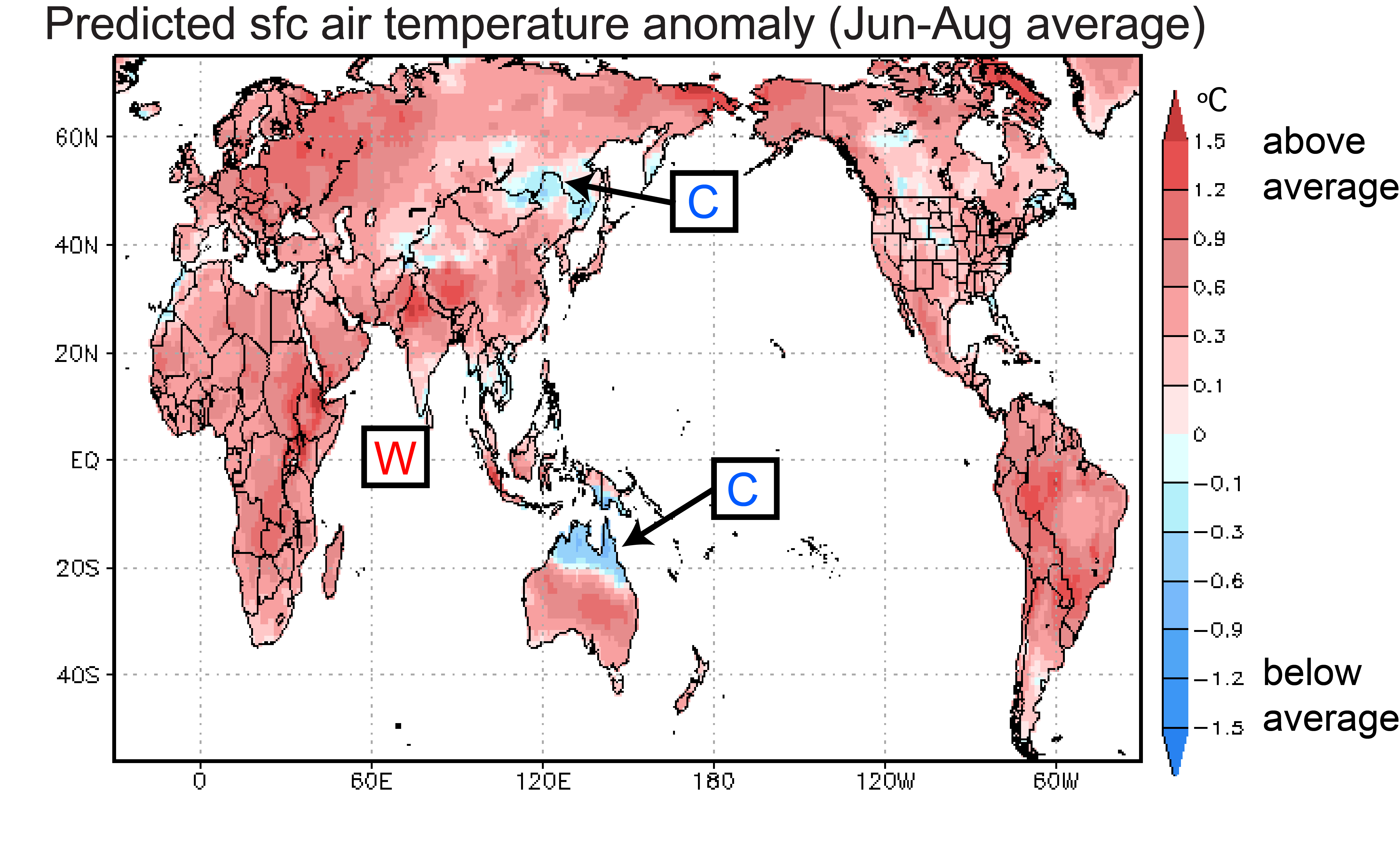

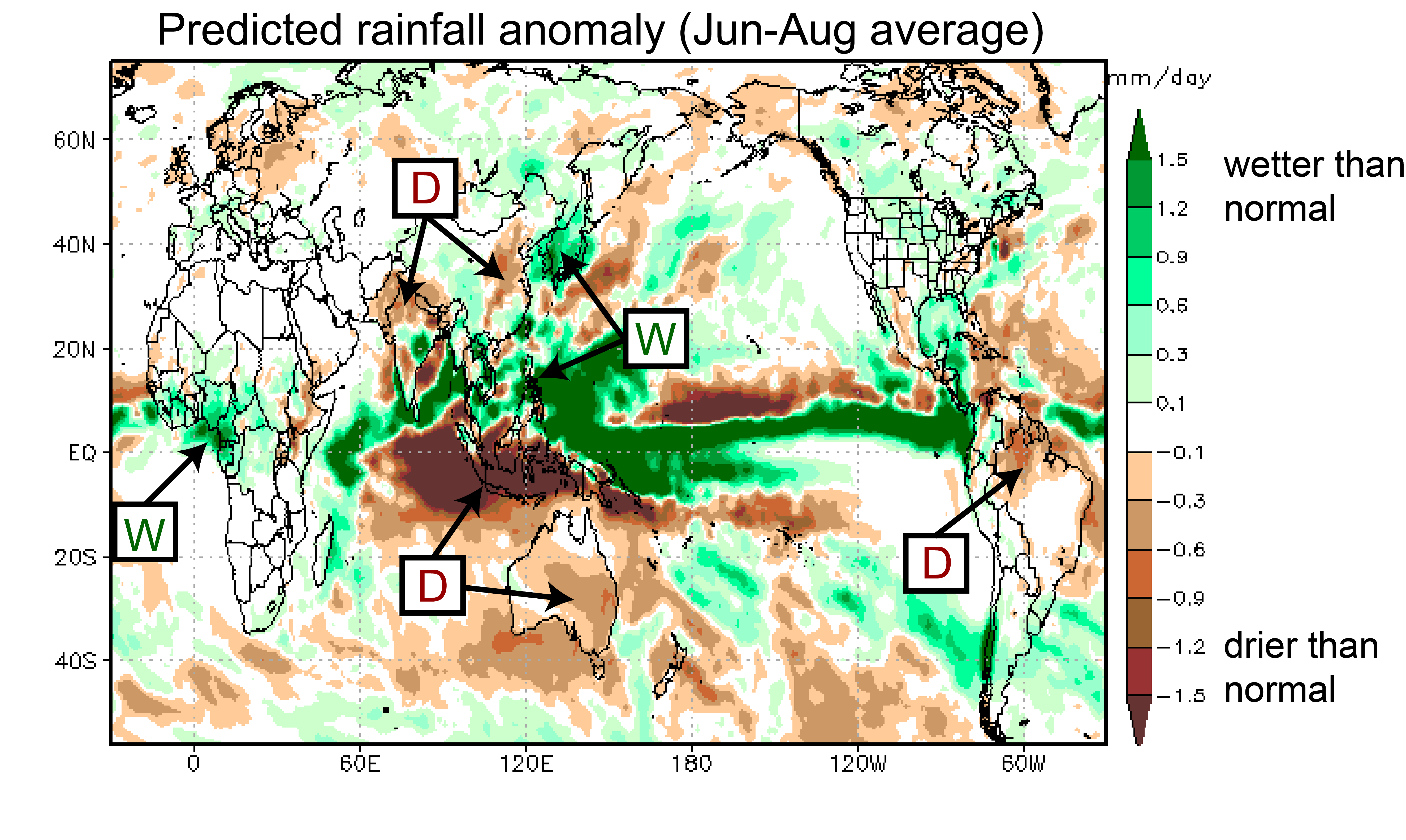

According to the SINTEX-F model, surface air temperature will be above average in most parts of the world, except for southeastern Russia and northern Australia. Rainfall is predicted to be above average in East Asia, Southeast Asia and West Africa, and below average in northern Brazil, Indonesia, Australia, eastern China and India.

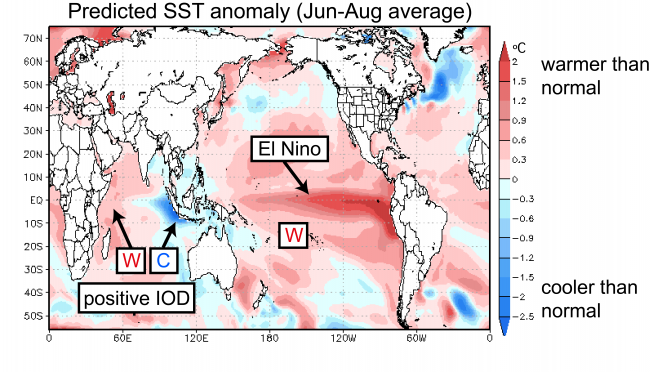

The tropics may play an important role in these rainfall patterns. Temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific are predicted to rise, which constitutes an El Niño event. In the tropical Indian Ocean, a positive Indian Ocean Dipole event is predicted to occur, with ocean temperatures warmer than average in the west and cooler than average in the east. The combined influence of these events should suppress convective activity over the eastern Indian Ocean and the Maritime Continent.

Based on the previous simultaneous occurrence of El Niño and positive Indian Ocean Dipole in 1997 and 2015, we expect widespread climate anomalies to occur.

Air temperature and rain forecast for the period June through August

As stated above, surface air temperature (Fig. 1) is predicted to be above average in most locations around the world, with colder than average temperatures predicted in a few locations only, including southeastern Russia and northern Australia.

Rainfall for the period June through August (Fig. 2) is predicted to be above average in East Asia, Southeast Asia and West Africa, and below average in northern Brazil, Indonesia, Australia, eastern China and India.

For Japan, the model predicts slightly warmer than average temperatures and above normal rainfall for the summer. Please bear in mind though that the model’s forecast skill in the mid and high latitudes is rather limited.

Ocean temperatures for the period June through August

In difference to daily weather fluctuations, seasonal climate variations are strongly influenced by changes in sea-surface temperatures (SSTs). Particularly in the tropics, where the SSTs are warmer than in other regions, even small changes in temperature can produce far reaching effects.

According to the SINTEX-F prediction, SSTs in the eastern tropical Pacific will rise above average during the summer, indicating the development of an El Niño event (Fig. 3). The eastern tropical Indian Ocean will become cooler than average, while the west will become warmer. This suggests that a positive Indian Ocean Dipole event will develop.

In Japan, the simultaneous occurrence of these two phenomena is expected to lead to cooler than average temperatures in northern Japan, and warmer than average temperatures in western Japan. This pattern is also known as “hoku-rei-sei-sho” [literally: north-cold-west-hot]. El Niño tends to weaken the Ogasawara High (a high-pressure system southeast of Honshu Island), and this tends to produce instability, rain, and cooler temperatures over northern Japan. Western Japan, on the other hand, is dominated by the positive Indian Ocean Dipole, which overrides El Niño’s influence and leads to hot temperatures.

A simultaneous El Niño and positive Indian Ocean Dipole have only been observed twice: in 1997 and in 2015. Thus, statistically speaking, there is little guidance to tell which influence will dominate.

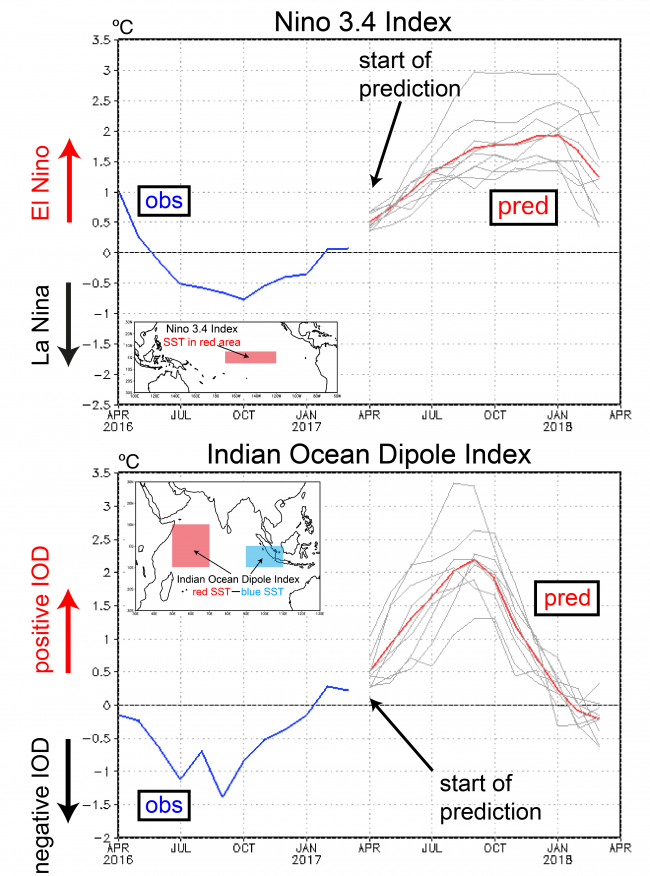

For the longer-term outlook of the two tropical basins let’s take a look at Figure 4, which shows two indices of interest. The Niño 3.4 index is predicted to exceed +0.5 °C in April and +1 °C in June (red line in the upper panel of Fig. 4), with the peak occurring in the following winter. As we mentioned before, if indeed another El Niño were to develop in 2017 it would likely put an end to the spell of La Niña-like conditions that have prevailed over the last 10 years or so. Instead, we might be entering a prolonged period of El Niño-like conditions. This would most certainly mean the end of the so-called “hiatus” in global warming and usher in a period of accelerated warming.

The IOD index is predicted to exceed +0.5 °C in April and 1 °C in June, with the peak occurring in fall. Note, however, that the ensemble spread (grey lines in Fig. 4, lower panel) is very large, so it is still quite uncertain exactly how strong this event will be.

Abnormal weather and climate events are not only influenced by El Niño/La Niña but also by the Indian Ocean Dipole. The simultaneous occurrence of El Niño and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole raises concerns for droughts developing in Indonesia and Australia. Further development should be closely monitored.