Quick summary:

- tropical Pacific predicted to be below El Niño threshold until end of the year

- strong positive Indian Ocean Dipole predicted to develop until fall

- enhanced risk of drought in Indonesia and Australia

- outlook for Japan: slightly warmer and drier than average in fall

Another hot summer has arrived in Japan, though some regions of Japan, particularly in the north, are still experiencing heavy rain. According to the JMA, temperatures in eastern Japan were above average in June, while rainfall was below average (link to the Japanese website). If these conditions continue we will have to worry not only about heat strokes but also about water shortage in the Kanto region.

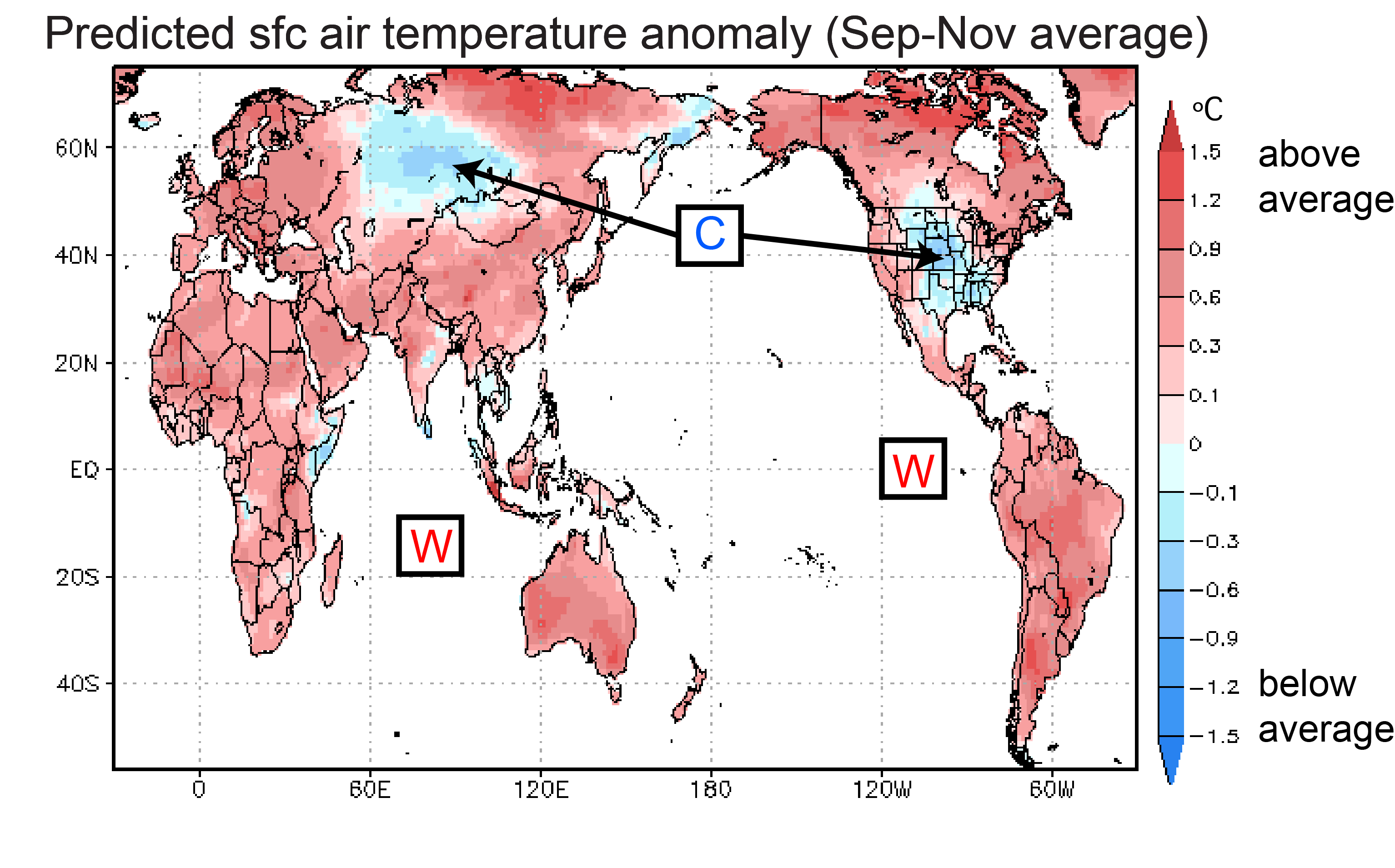

Let’s take a look at the latest predictions. According to the SINTEX-F model, surface air temperatures over land will be above average around the globe from September through November. Two notable exceptions are central Russia and the central US (no political message intended here).

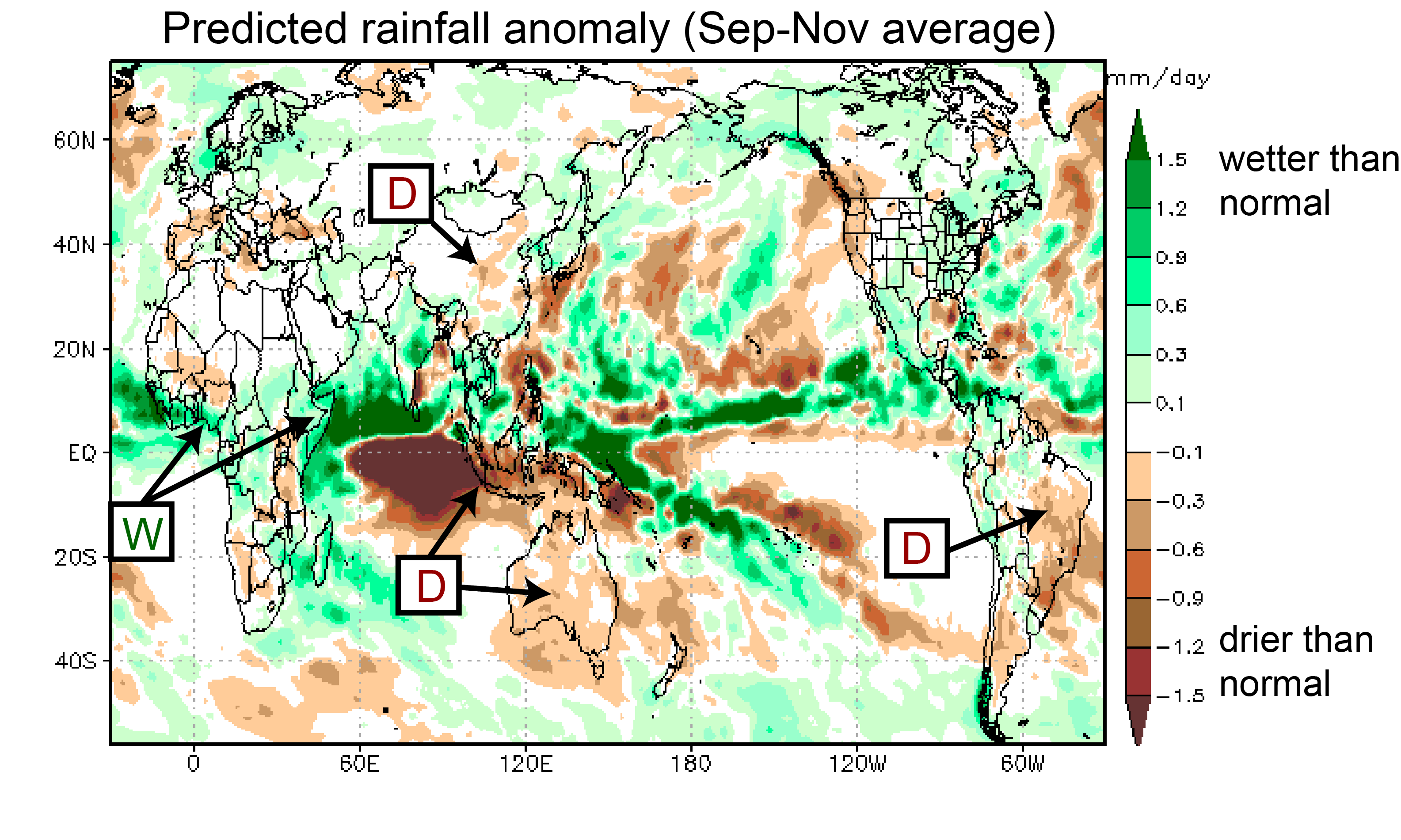

Rainfall for the period September through November is predicted to be above average over tropical Africa. Below average rainfall is predicted for Indonesia, Australia, and most of Brazil.

For Japan, the model predicts slightly warmer and drier than average conditions in fall. Please bear in mind though that the model’s forecast skill in the mid and high latitudes is rather limited.

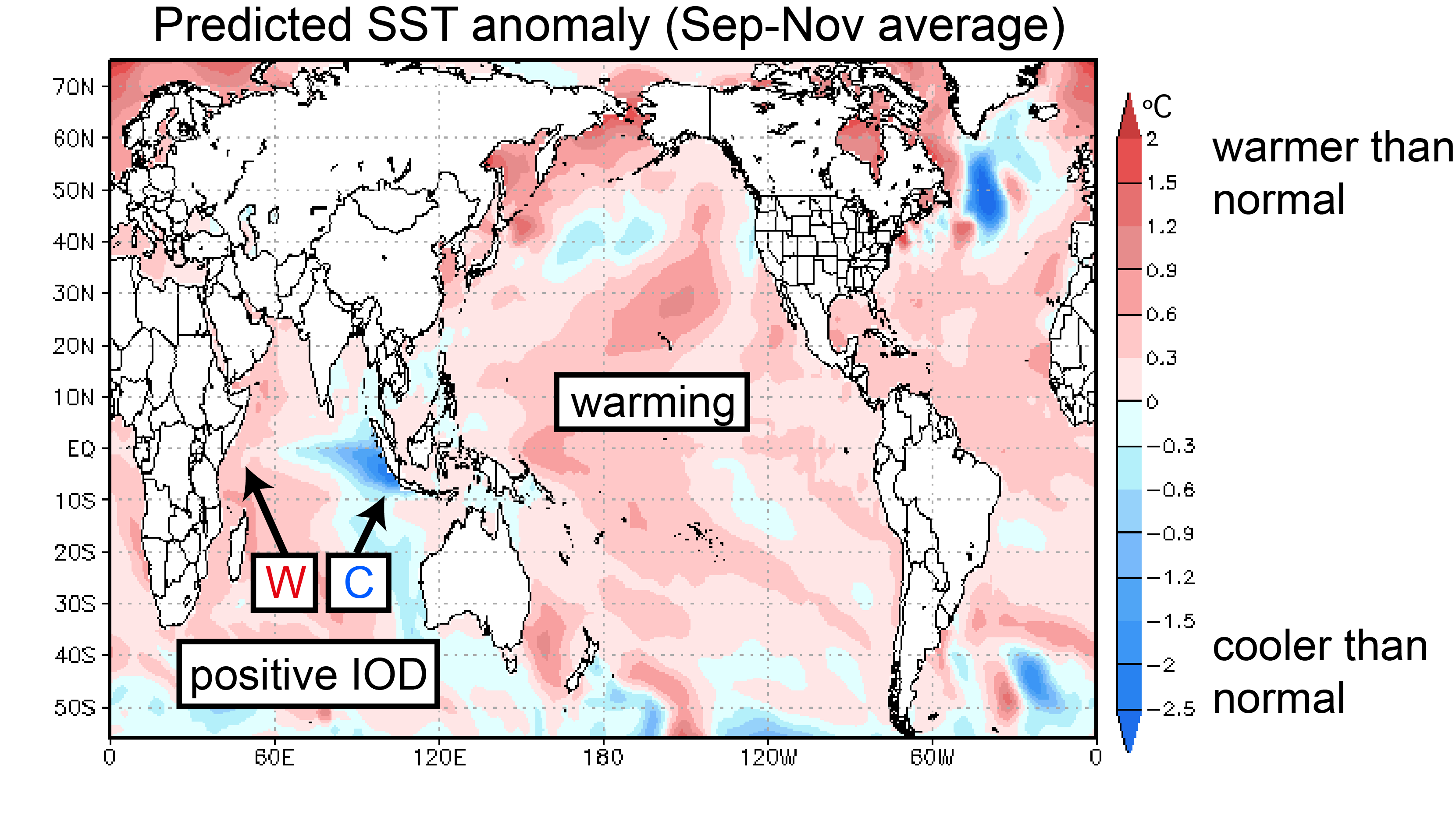

Sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) in the entire tropical Pacific are predicted to be above average for the period September through November. Accordingly, temperatures in the Niño 3.4 region will also be above average but will not rise above the 0.5 °C El Niño threshold.

In the Indian Ocean, on the other hand, the model continues to predict the development of a strong positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) event, with cooler than average SSTs in the east, and warmer than average SSTs in the west. Positive IOD events (particularly the lower than average SST in the east) tend to suppress convection over the eastern Indian Ocean and the maritime continent. The predicted drought conditions over Indonesia and Australia are consistent with this.

Positive IOD events typically lead to warmer than average temperatures in western Japan. We therefore expect that the remote impacts of the positive IOD will lead to a strengthening of the Ogasawara High (also called Bonin high) and warmer than average temperatures (not shown).

What is the extended outlook for the tropical oceans?

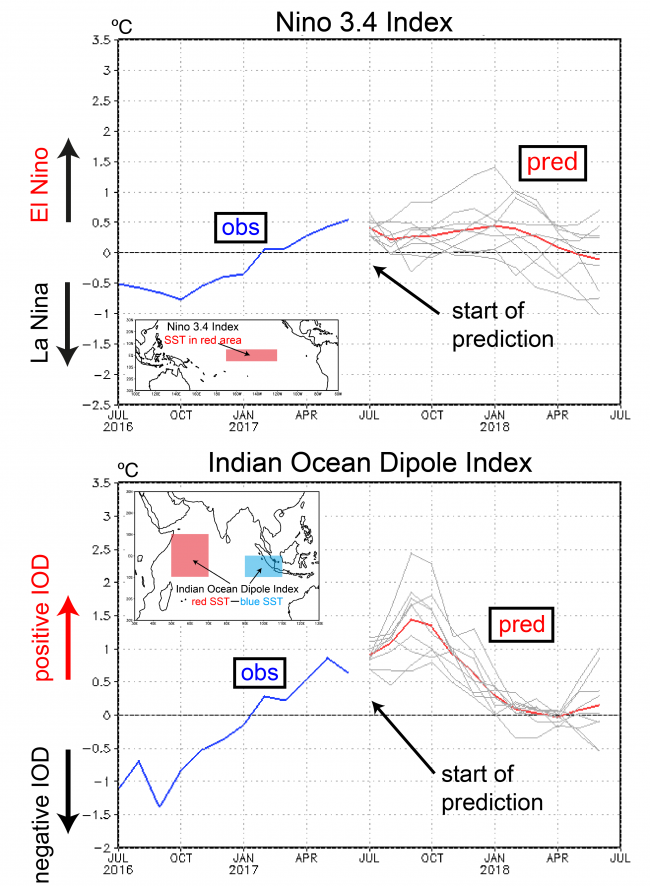

Figure 4 shows two SST indices of interest. The Niño 3.4 index is predicted to approach the +0.5 °C El Niño threshold in January but not exceed it (red line in the upper panel of Fig. 4). Thereafter, it will decline with temperatures slightly cooler than average in the spring of 2018.

The IOD index is predicted to peak at + 1.5 °C in September (Fig. 4, lower panel). In the following months it will gradually decay, with neutral conditions setting in during winter.

A few more remarks on the remote impacts of the IOD. As noted above, positive IOD events tend to bring high surface pressure to Japan, with warmer than average temperatures and lower than average rainfall. The currently predicted tropical SST pattern (neutral Pacific + positive IOD) has precedents in the recent past. In 1994, Japan was under the influence of high pressure systems that reduced rainfall and contributed to record breaking heat waves. In 2006, Australia was hit by an extremely severe drought that devastated the wheat harvest. The current predictions therefore raise the concern for droughts in Indonesia and Australia.